Part II of the story from that time I nearly died in Tajikistan’s Pamir Mountains. Don’t miss part one, which includes assault by mutton, brain failure, and a scenic 4-hour off-road techno jeep ride to the hospital.

Beautiful as it is, Murghab should not exist.

Before Tajikistan’s highest town (3,650 m) came into existence, the remote region’s only inhabitants were a smattering of Kyrgyz nomads.

Then the Soviets came, building Murghab to stake out their territory near China and Afghanistan. Thousands came to profit from the nearly 100% employment rate, but after the Soviet Union’s collapse, “limping on” would be a generous descriptor.

Nothing grows in Murghab, save a few sparse grass patches and shrubs around a winding river tainted by animal feces. Jobs are as scarce as plant life, as is affordable fuel for heating during biting winters. Virtually everything must be shipped in from nearby Kyrgyzstan, to be sold in a shipping container bazaar to residents who barely have enough money to pay.

An appropriately desolate place to confront my mortality, I must say.

Murghab’s shipping container bazaar

One breath of fresh air, please

After my literal crash landing into Murghab hospital, I lied on a hospital deathbed of roses—“So Very Lovely” rose-patterned sheets—and waited for salvation.

Half an hour had passed since I haltingly requested oxygen in Russian, but there were no signs of success. Russian is a difficult language at the best of times; it is assuredly more difficult when your brain is failing, your head is screaming, and you’re pretty shit at Russian to begin with.

Shakily, I sipped from a possibly-parasitic mug of water. At least I’ll die hydrated. My skin will look so good at my viewing.

Rattling wheels eventually announced relief: a bespectacled nurse wheeled in an oxygen machine.

Peeling medical tape secured the oxygen cartridge to the mount; a dirty handkerchief propped it up from the bottom. The nurse went to plug in the machine, then realized there were no outlets. I had to be half-carried to another room where there was, in fact, electricity.

Finally, tubes wrapped around my head and poked into nostrils. A whirring purr indicated oxygen was finally returning to my body (… almost one hour after entering the hospital). For the first time in what felt like a lifetime, my head hurt slightly less.

Wrapping myself in my new bedcover—mystery stains and geometric patterns with “LOVE” in bold black letters this time—I lied back to savor breathing and reassurance that I (probably) wouldn’t die that day.

A very out outhouse

Hearty doses of mystery painkillers and a full cartridge of oxygen subdued my exploding head for a time. The bespectacled nurse—let’s call her Specs—came periodically to check vitals and make sure the ancient oxygen machine was still functional.

To save me (or himself) from my abominable Russian, the head doctor instructed an English-speaking patient named Aika to help should I need anything. Chirpy and excited to flex her language skills with a foreign tourist, the Kyrgyz twenty-something fussed about, fetching tea and fixing my bed sheets as she flexed her English skills.

She was too sweet, I was too brain dead, noises were too painful—I guiltily asked her if I could rest. She left me alone, insisting I shout if anything was amiss. I lied back on my LOVEbed and stared at the ceiling like the oxygenated vegetable I was.

Relaxation proved elusive. More pressure was building in my body… but this time, below the belt. A moment I was dreading finally arrived: I had to pee.

There was no point in postponing the inevitable, but I could barely stand, let alone walk. The physics of a toilet trip in my current state were beyond me, but I couldn’t deny nature’s call. I asked Aika where the toilets were and she eagerly launched from her bed to show me the way.

Rather than leading me further into the hospital, Aika took me by the arm and steered me down the hall I entered from and… out of the hospital? Dazed and confused, she supported me as I stumbled slowly in the evening darkness.

Left, right, don’t fall over, left, keep breathing, right… wait, what, how far are we going?!

Climbing the meter-high hill outside the hospital felt like summiting Everest; I was gasping as we moved toward a small white building… but trivialities like breathing were soon forgotten upon entry.

Theory: front hole is for vomit

Vomit, blood, urine, feces, bleach, mystery; every bodily and/or foul fluid on earth was splattered across the floor and walls of the open toilet stalls. An alarming stench rose up from the oversized and oddly-placed triangular toilet holes—large enough to fall in, I noted—as large flies buzzed happily around the cesspits.

On the bright side, the threat of death by drowning in excrement provided me with just enough adrenaline to squat and empty my bladder without collapsing.

Situations like these can be overwhelming in times of stress; the key is to stay calm and be logical. Practically speaking, the toilet situation was relatively unproblematic. The real problem was the total lack of soap and running water in the Murghab hospital, as I learned a few minutes later.

Face down, ass up

My toilet success lulled me into a false sense of security, but my suffering was far from over. Just when things seemed to be clearing up , my head exploded in full force once more.

I couldn’t open my eyes; the room’s single incandescent light bulb was more blinding than the sun. Aika’s conversation with the only other patient in the room—a Kyrgyz woman in her 50s with a high-pitched Shirley Henderson voice—was worse than a symphony of nails on chalkboards.

I tried to roll over and cover my ears with my pillow, but every movement was sheer agony. I cried out in pain as my brain seemingly sloshed against the walls of my skull.

Aika ran off to find a doctor. Approximately one eternity later, she returned with an old man in a dirty gray sweat suit. A nurse? A lost patient? Neither, it turns out: he was the surgeon on night duty. Sweatpants and scrubs aren’t so fundamentally different, I suppose.

After apathetically taking my vitals, he looked at me indifferently.

“Nothing is very wrong with you. You have only small fever.” At least we could speak in English.

“I am not okay.” My head hurts very, very much, I added in Russian for emphasis. Aika reprimanded the doctor in Kyrgyz, and he disappeared, eventually returning with Specs the nurse. Horror quickly replaced relief. Specs carried a metal tray filled with medicine… and syringes without packaging.

I don’t need electricity. Squat toilets from hell are fine. But every traveler has to draw a line somewhere, and mine is at potentially reused syringes. Despite pain, I recoiled as Specs picked up the needle.

What is that? I asked warily in Russian.

“Dexamethasone,” Dr. Sweatpants sighed impatiently, “for brain swelling.”

I paused. Seemed reasonable; a swollen brain would explain why my head was about to blow. I weighed my options:

- Survive with HIV forever.

- Die by brain blast in remote Tajikistan hospital.

Preservation instincts kicked in; I’ll take life with HIV for $1,000, Alex. Hesitantly, I offered my left arm.

“No,” Dr. Sweatpants shook his head, “Remove pants please.”

Shit. I was finally getting the gluteal injections I thought I’d so cleverly escaped in Shaimak.

Rolling over onto my side—slosh, slosh went my brain—I squeezed my eyes shut and tried to suppress my fear of needles for my first-ever anal injection. Cheeks clenched as I felt Specs swabbing with alcohol.

“Relax,” Dr. Sweatpants advised.

“I’m tryin—AHHHH!” I lost my composure and screamed as the needle slammed into my bum with far more force than anticipated, my body jerking in instinctual response.

“Not so bad yes?” Dr. Sweatpants asked cheerfully as I curled into fetal position and Specs gathered up her effects. “Now I will bring IV with some antibiotics. Just in case. You will feel better.” I would’ve rolled my eyes if I wasn’t at 9/ 10 on the pain scale. Add that to the list of Things That Should’ve Been Done Hours Ago.

One hour later, after a botched first attempt to insert an IV—turns out Specs was consistently ungainly with needles, and I got the bruises to prove it—fluids seeped into my veins, Dexamethasone deflated my brain, and oxygen pumped into my lungs. For the first time in more than 24 hours, I was… okay. Sweatpants was right: I did feel better.

Finally, for the first time in two days, I slept.

Deadly discoveries

The next morning brought progress: I could look at my phone for more than 30 seconds without searing pain.

While I watched a mangy stray cat lounge contentedly on a hospital bed next to mine, my phone buzzed: a message from my best friend, a medical student. In between panicked exclamations, she said based on my symptoms I probably had HACE. Clueless as to what that meant, I hit up another friend: Dr. Google.

Slowly I typed: what is HACE?

High Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE) is a severe and potentially fatal manifestation of high-altitude illness and is often characterized by ataxia, fatigue, and altered mental status. HACE is often thought of as an extreme form/end-stage of Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS).

Well that doesn’t sound too good, I thought nervously. I went on to clarify the symptoms of HACE as the stray cat went through his morning yoga routine.

- Altitudes higher than 2,000 meters? Check.

- Severe headache? Definitely.

- Lethargy, disorientation, and confusion? Check, check, check.

- Brain swelling? Dexamethasone worked wonders, so it seems so.

I scrolled further.

Usually fatal within 24 hours if untreated. Without treatment, the patient will enter a coma and then die.

… oh.

I’ve gotten sick plenty of times on the road, but death? No. Slowly, it dawned on me just how close I’d come to dying in the Pamir. Had my homestay host not convinced me to take the private taxi, I could’ve been dead on her floor by the end of the day. My backpacker thriftiness literally could have killed me.

Oh my god.

Note to future self: the next time you’re on the verge of death, just take the damn taxi you frugal fool.

Note: Don’t do what I did. Before traveling at high elevations, educate yourself on different forms of altitude sickness, treatment, and prevention.

My hospital companions: Aika and Cat

Three tales from Murghab Hospital

Days blurred. Injection cycles, painkiller doses, and visits from the stray cat were my only indicators of time. Though my brain was no longer exploding, I was too weak and uncoordinated to do much except lie in bed, ponder death, and submit myself to the eccentricities of Murghab Hospital.

1: Breakfast and bum jabs

Noticing I was alive, Kyrgyz Shirley Henderson and Aika invited me to breakfast with them. I hobbled over to their table to join their nutritious feast: stale bread, Nutella, condensed milk, and individually wrapped toffees and chocolates. Petrified bread with sugar wasn’t tempting despite not eating for more than 24 hours, but they were forceful.

As I gnawed on fossilized non and Nutella, Specs entered the room. Looking sternly at me, she pointed to my bum, brandishing another massive syringe. Gulp.

On the bright side, the morning’s needle was still in its wrapper. Despite the morning’s diabetic onslaught, at least I could rest assured I was HIV-free. Hopefully.

2: Money and marriage

The head doctor returned to check on me eventually. Sitting on the bed next to mine, he leaned in to talk, again in Russian. After some checkup questions and pleasantries, the real talk began.

Doctor, how much does all this cost? I asked nervously.

He looked thoughtfully at me. How much do you have?

Not much. I don’t have much money. There is no ATM, and the taxi from Shaimak was expensive. My cash is low, I explained.

It is about 1,000 dollars. But for you, less.

My eyes bulged. One thousand DOLLARS?! The doctor roared with laughter.

It is free. You can stay here as long as you like. Groaning at his poorly timed joke—and my groggy inability to detect humor—I sank into my pillows in relief.

Alexandra, are you married? he continued on after watching me pointedly for a moment.

No…. why?

Because you are very beautiful, he smiled flirtatiously, do you need a husband?

I don’t need a man. I stared back with the best bitchface I could muster. I need more oxygen.

The hospital pharmacy. Doctors recommend medications, the patient goes to buy them, then the doctor administers them. Aika was kind enough to go buy my medications for the first couple days when I was too weak.

3: Routine throat maintenance

Shortly after relocating to the third room of my visit—a small blue double with Aika—a new female doctor entered to check on me. Her Kyrgyz features were sharp, but her voice was gentle. She carried a tray of instruments with her.

“Does your throat hurt?” she asked in English.

“No?” After days of anal injections and oxygen cartridges, I wasn’t sure why throats were of concern.

“I am going to clean your throat,” she announced. No discussion.

Brandishing a long pair of tweezers, she pinched a large wad of gauze, dipped it daintily into a bottle of iodine, then loomed over me. “Open,” she ordered.

“WHa….?” The moment my mouth opened, she pushed my head back, scrubbing the back of my throat with the iodine gauze as I gagged and spluttered.

“Good. Now your throat is clean.”

Satisfied, she packed up and marched out of the room, leaving me with just as many questions as when she arrived.

There’s no food at Murghab Hospital—patients families bring them food—but Aika was kind enough to share her food with me. Breakfast that day: old bread ripped into pieces and soaked in hot milk tea.

Looking for lesser evils

Three days passed. My brain fog lifted, but the future was still unclear.

Problem was, I was racing the clock. In less than 10 days, I had to co-lead my first ever women’s tour of Pakistan. Despite my near-death adventures, I needed to get my ass in gear and move from Tajikistan to Pakistan ASAP. But… how?

As morning light trickled through my hospital window, I weighed my two clearest options:

Option 1: My original plan was to hitchhike with truckers over the 4,363 meter (14,000 ft) Qolma Pass into China, the only way to cross the Tajikistan-China border and one of the highest crossings in the world. Next, I’d have to take a bus over Khunjerab Pass—the highest paved border crossing in the world at nearly 5,000 meters above sea level—into Pakistan. Then, to get to Islamabad, Pakistan’s capital, I would have to bus over the 4,173 m Babusar Pass.

Babusar Pass, the lowest of the three potential passes

Considering my recent brush with potentially fatal altitude-induced illness, option 1 didn’t seem overly sensible. There was also a slight logistical issue: I was physically incapable of lifting or carrying my backpacks, let alone climbing into trucks with the 30 kg packs. I needed an alternative.

Option 2: Fly to Pakistan.

According to Dr. Google, flying would probably be safe in my condition. Despite my disdain for flying (for climate, cost, and entertainment reasons), it seemed more plausible than passing out at a Chinese border crossing post. But… how? Murghab had no functional airport. Dushanbe, Tajikistan’s capital, was a 20+ hour drive over more soaring Pamir Highway passes. Neighboring Kyrgyzstan’s international airport in Bishkek was even further afield.

When in doubt, wait it out. I decided to bide my time until an answer revealed itself.

Luckily, I only had to wait an hour.

Exchange epiphanies

After another prehistoric portion of fossilized non for breakfast, Aika announced she was going to help a Korean tourist change money. I sat up quickly. A money changer in Murghab? I’d run out of Tajik somoni, and I needed more cash to pay for medicines and anal injections.

Together with a middle-aged Korean cyclist—hospitalized with a broken arm after crashing on a loose downhill track—we walked across the street to a modest, cream-colored microfinance bank.

That 100-meter walk felt like a marathon.

Breathing heavily and almost too dizzy to stand, I put some of my last dollars on the teller’s counter… then put my head down next to them. Rushing noises muffled my ears; a sign I was on the verge of passing out. Something about an exchange rate penetrated the noise; I waved my hand weakly to indicate any rate was fine as long as I got money somehow. Several hundred somoni slid under my elbow.

My answer was clear: after days of illness at more than 3,600 meters above sea level, it was time to go lower. ASAP.

Taxi to salvation

“Aika, how do I get to Osh?” We’d made it back to the hospital, and I was watching my roommate and now-friend pack up her belongings to return home.

I’d done my research. Osh, the closest Kyrgyz city and supplier of all of Murghab’s sort-of-fresh produce, was a tantalizing 963 meters above sea level. More than 2,500 meters lower. I vaguely recalled a traveler saying it was about 8 hours away, which seemed manageable. I could be at a safe altitude by the end of the day.

Salvation waited for me in Osh. I was sure of it.

Aika looked up from packing her bag. “There is share taxi from Murghab. I think not so expensive. But no go to Osh!” she pouted, “You stay at my home instead.”

Her invitation was tempting—I do like hanging with friendly local women as mothers dote on me with homemade food—but my time was ticking.

Plus I feared dying on her living room carpet; corpses don’t make good house gifts.

I apologetically declined Aika’s invitation, but she was persistent. We made a deal: I’d come to her house for a few hours to wait for my taxi to salvation.

Done.

The plus side of being hospitalized while the verge of death is that it makes packing straightforward: I hadn’t changed my clothes in days so there wasn’t much to pack. Aika called a driver, and 20 minutes later we piled into a dusty red car-cum-taxi outside the hospital.

I didn’t look back as we drove through the gates. Goodbye, Murghab Hospital. If we ever meet again, it will be too soon.

Before we could go home, first things first: I needed a shared taxi seat. Murghab’s taxi stand, like most in Tajikistan, is more a place where taxi drivers stand than an official taxi stand. The little red car rolled to a stop on a roadside and Aika hopped out, waving at men squatting in the shadows of a nearby building. I got out and leaned against the car to listen. Concerns about being ripped off superseded my utter exhaustion.

After a brief discussion in Kyrgyz, Aika turned to me. “There is one seat left on taxi today. You sure you want? You don’t want stay my home?”

You are an angel, but I would kill puppies if it means I can descend today. “Yes, I am sure. Thank you, Aika.”

Another discussion ensued, then it was confirmed: I had a seat. The taxi driver would come pick me up at Aika’s house in an hour. I was going to Osh that day.

Maybe, just maybe, I wouldn’t die in Tajikistan after all.

Aika’s family home

It’s beginning to look a lot like Christmas

The little red taxi dropped us at Aika’s house, a typical Murghab affair: low, cement and stone, painted white.

Ignoring her young brother’s gaping at the foreign invader, Aika led me into a plush sitting room lined with pillows, carpets, and trinkets. I settled onto some cushions—dying here wouldn’t be so bad, actually—as Aika prepared me a welcome tray of snacks despite my pleas not to. Hospitality is paramount, even if you’ve just returned from the hospital.

She rattled into the room with a tray of hot tea, a mixed plate of sweets and biscuits, homemade butter and (still petrified) bread, and a bowl of a caramel-brown substance I’d never seen before. She handing me the mystery bowl first, smiling. “You must try, it is my favorite!”

The overpowering aroma of sheep filled my nostrils as I sniffed experimentally.

“… it is made from mutton fat!”

Curse the mutton gods.

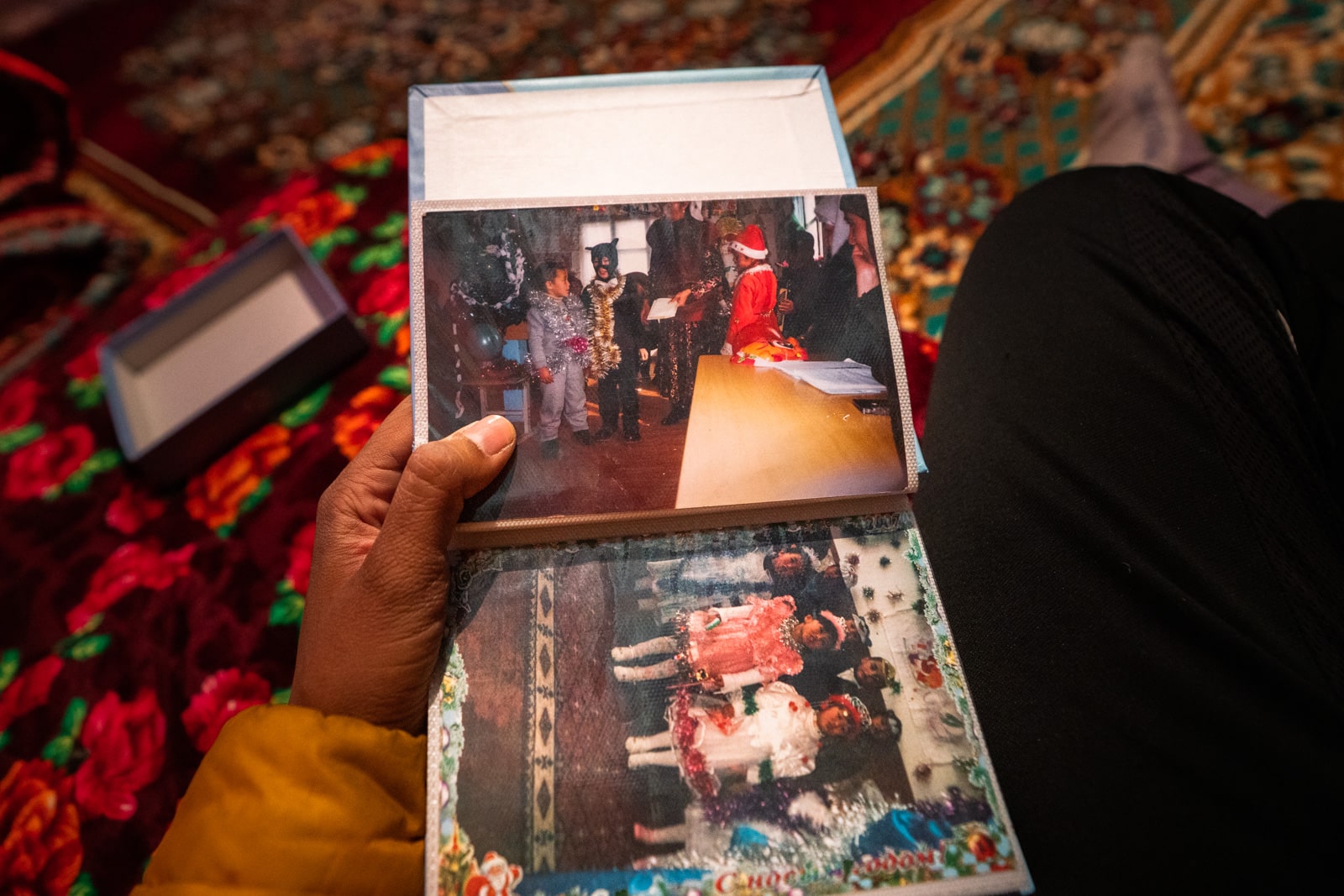

Luckily, Aika was too busy rummaging for her next exhibit—a family photo album filled with everything from Kyrgyz weddings to an explosively tinseled primary school Christmas party—to notice the barely-touched bowl of fat.

Wholly focused on ignoring the sickening scent of mutton, I gnawed fruitlessly on buttered bread and flicked through Christmas photos as Aika chattered away while kneading (fresh) bread dough.

What’s more Christmas than Muslims celebrating with tinsel decor and Batman costumes? (Answer: Christmas in Kolkata, India)

Don’t let my intense disdain for mutton mislead you; the situation was bittersweet. Though I was looking forward to actually breathing, I was sad to leave Tajikistan so soon. My heart was heavy as I listened to Aika make plans for a future (hopefully illness-free) rendezvous in Kyrgyzstan. At least I had good company in my final hours.

Thanks again, Aika, for saving me in multiple ways.

Crunching pebbles announced the arrival of the shared taxi. After one final plea to stay, Aika helped the driver load my bags onto the roof, and we hugged tightly as a final goodbye.

By the grace of god—or foreign privilege—the shared taxi’s occupants left me a seat in front. Murmuring tired thanks in Russian at the 9 Kyrgyz faces crammed into the back two rows of the jeep, I squeezed in between the driver and an old woman in a bulky wool coat.

As the car roared to a start, the old woman smiled broadly, taking my hand in hers and clasping them in her lap. Reassured by her gentle touch, I began to relax. After six days of being bedridden by fever and extreme altitude sickness in the Pamir, I was finally—finally—going down. In less than 8 hours, all would be well.

… or so I thought. Wrongly, I might add.

Head on to Part III for the final sloppy installment.

Safety note on altitude sickness: Humor aside, I now understand this experience could have been fatal or caused lasting brain damage. Altitude sickness (AMS), especially advanced forms like HACE, are a serious risk when traveling the 3,000m+ Pamir Highway. You must be careful when traveling at high altitudes: avoid sleeping more than 1,000m higher than the previous night; stay hydrated and do not overexert yourself; pack AMS medications such as Diamox (if you’re not allergic to sulfa) and dexamethasone in the event of HACE. Most importantly, educate yourself on symptoms of different forms altitude sickness and treatment options should any occur.

You are so brave!

Você é muito Corajosa!

I don’t know about brave so much as stupid in this case ?

Part two was worth the wait and I am glad you did not die 🙂 Now can’t wait for part three! I live in Belgium, we can meet and you can tell me in person if it takes too long to write, because I can’t waaaait 😀

I’m glad, too ? Where in Belgium do you live?

Thanks for part 2,looking forward to 3. Being sick on the road sucks. Have been Violently ill on treks in Nepal and India, with Hace and Dysentery ,not fun

Oooof, neither are good companions for trekking. Did you keep on trekking?

Brussels (how original) 😀 I recently commented on your post about climate change, piccola_reporter on Instagram!

I cant even bring myself to imagine that there’s still more to this horrifying experience!!! Waiting anxiously for part 3…

P.S. Aika has such a cheerful and reassuring sort of presence. Loving her!

Dear Alex,

I am really sorry you got so sick and couldn’t persue your initial plan in the Pamirs. But luckily you were all right again in the end and found a way out of the High Pamirs.

Funny that you mentioned Pshart Valley. I was doing the Pamir Highway and the Wakhan Corridor with a group last summer and we also stayed with a nomadic family in Pshart Valley.

Luckily no one from your group got any altitude sickness. I hope you will be able to go to the High Pamirs again one day without getting sick. It’s such a beautiful and fascinating part of our planet. And you MUST got to Pshart Valley then 🙂

Kyzylart Pass (4’280m) is probably the explanation for Part III.

Regarding altitude sickness, the safe recommandation is “upper than 3’000m altitude, avoid sleeping more than **400m** higher than the previous night”. 1’000m is far too much risky for most of us. In case you can’t avoid an altitude difference bigger than 400m, keep a 400m / day average for the 2 consecutive nights. Meaning, no more than 800m total. For instance, night 1: +600m, night 2: +200m.

During a trekking day, you normally could hike really high (for instance for pass crossing) as far as you sleep low enough at night.

Fabrice

luckier than you at Murghab, since I was coming from Langar (Wakhan).

I did experience the Qolma Pass the next day (in case you need my feed-back)

I had same experience when my husband and I flew directly from Lima (altitude: 1,550) to Titicaca (altitude: 3,813m). It was really scary altitude sickness experience. It is really important to be careful and plan carefully. I am happy you are ok now Alex. God Bless all the people who helped you in the hospital.

I remember following this journey on your insta stories. What can I say? I couldn’t say anything on that day. I am not sure what to write today. Just be safe, very very safe. We have to meet in Kolkata someday, you promised!

When is part 3 being published?