A firsthand look into the history of Patan Patola one of the most complex woven art forms in India… and the world.

Two fluorescent bulbs cast harsh shadows on the peeling walls of the cramped workshop in Patan, a town in India’s Gujarat state. Eight workers sit inside, silently focused on the tasks at hand: carefully wrapping and unwrapping thousands of dyed silk threads.

A middle-aged man, Mr. Soni, stands at the center of it all, a master watching over his craftsmen. And watch he must: if one mistake is made, the process must begin all over again. Such is the art of Patola, India’s most complex textile.

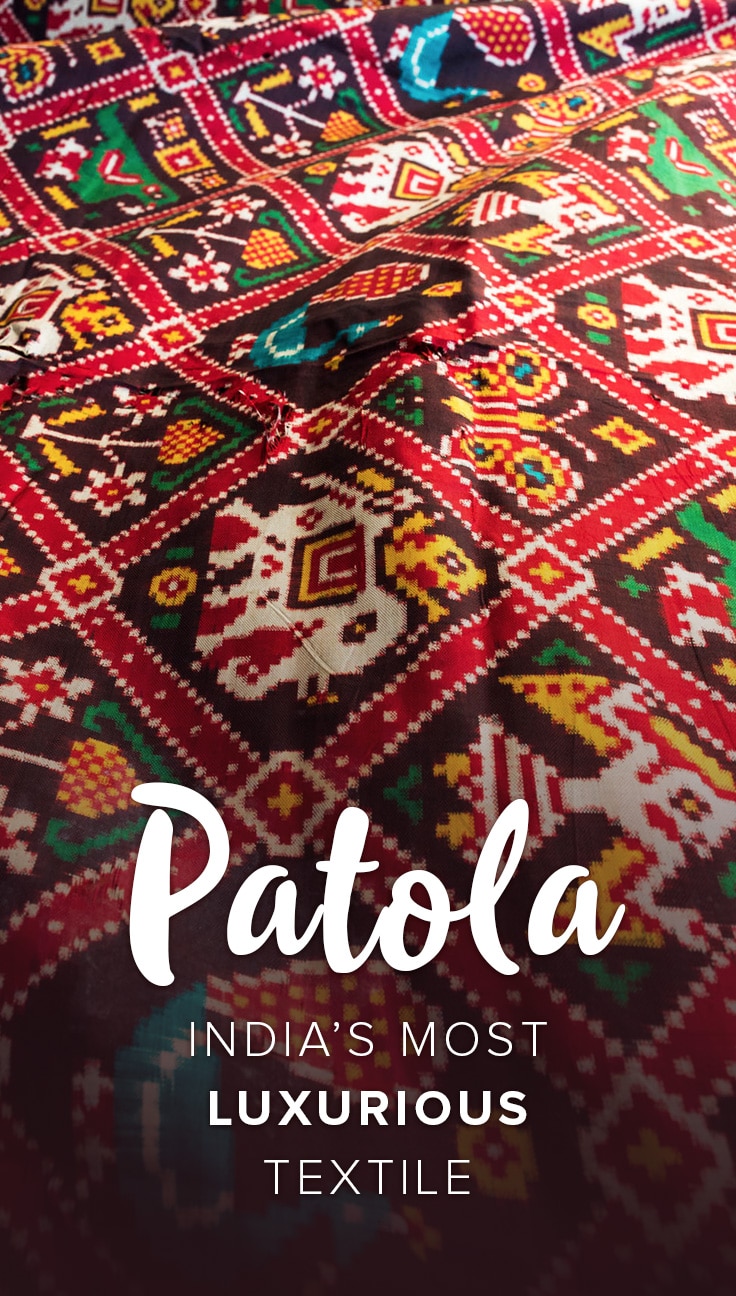

This classic Patola is already 60 years old… and still lookin’ good.

Patan Patola: cloth of kings

The complexity and time-intensiveness is what makes Patola so valuable. A dizzyingly mathematical process, Patola saris are woven using dyed threads both vertically (warp) and horizontally (weft) to create the design. The strings are dyed according to a pattern, and the dye marks align when woven, forming the pattern on the cloth.

(If you have no idea how weaving works, that’s okay. TL;DR this process is insanely difficult.)

Each Patola begins as a hand drawn pattern

For each color in the design, workers tie sections of the silk threads with cotton string until only the parts to be dyed remain exposed. The whole bundle of threads is then soaked in dye, before the cotton strings are torn off to reveal the un-dyed portions. Rinse, repeat, until the threads are all dyed to match the pattern.

The first round of wrapping. Note the grid system marked out along the threads.

The wrapping and dyeing process for just one color takes a week, and doing all the colors takes one or two months. Mr. Soni tells me how, from start to finish, designing and making one saree takes at least seven months.

Our jaws hit the floor, but it’s standard procedure for Mr. Soni. To put things in perspective, he tells me the most difficult sari they ever made took 2.5 years. But the price tag on a Patola sari justifies the days of painstaking work: one custom-made sari starts at 150,000 rupees, about $2,250.

After watching the workers nimbly tie and untie threads for half an hour, we’re chomping at the bit, excited to see everything come together in the weaving rooms. But Mr. Soni leads me away from the workshop instead.

He insists we make a quick stop before he reveals the rest of his workshop’s secrets. “It’s important, first, that you understand the story of Patola.”

The town of Patan in Gujarat, India

The history of Patan Patola

The story begins more than 900 years ago, with a king named Kumarpala.

The king had a passion for Patola, one of the most luxurious textiles in the world. Woven so well that the front and back are indistinguishable from each other, and a colorful feast for the eyes, they were truly the cloth of kings, and the ultimate symbol of wealth.

Kumarpala was particular about where and when he donned his Patola. A patron of Jainism, he needed to be clean and dressed in fresh clothes before saying prayers at the temple. In a display of extreme piety (… or royal indulgence), he insisted on wearing only Patola when visiting temples.

Initially, his Patola supply came from Jalna, a city in neighboring Maharashtra state. That screeched to a halt once Kumarpala learned how the king in Jalna used Patola as bed sheets before selling or gifting them to other aristocrats in the region. The Jalna king’s ego aside, what kind of king knowingly wears the bedsheets of another?

The royal problem was resolved in a suitably royal fashion. Furious and determined to have an untainted supply of Patola, King Kumarpala brought 700 Patola craftsmen and their families to Patan, Gujarat, from Maharashtra and Karnataka states. It’s said that he then staggered production, and despite the 7+ months manufacturing time of Patola, he received at least one new Patola to wear to the temple every day.

Kings will be kings.

Want to know more about India? Check out our assortment of blog posts on India!

Patan has more than just Patola!

Patola now

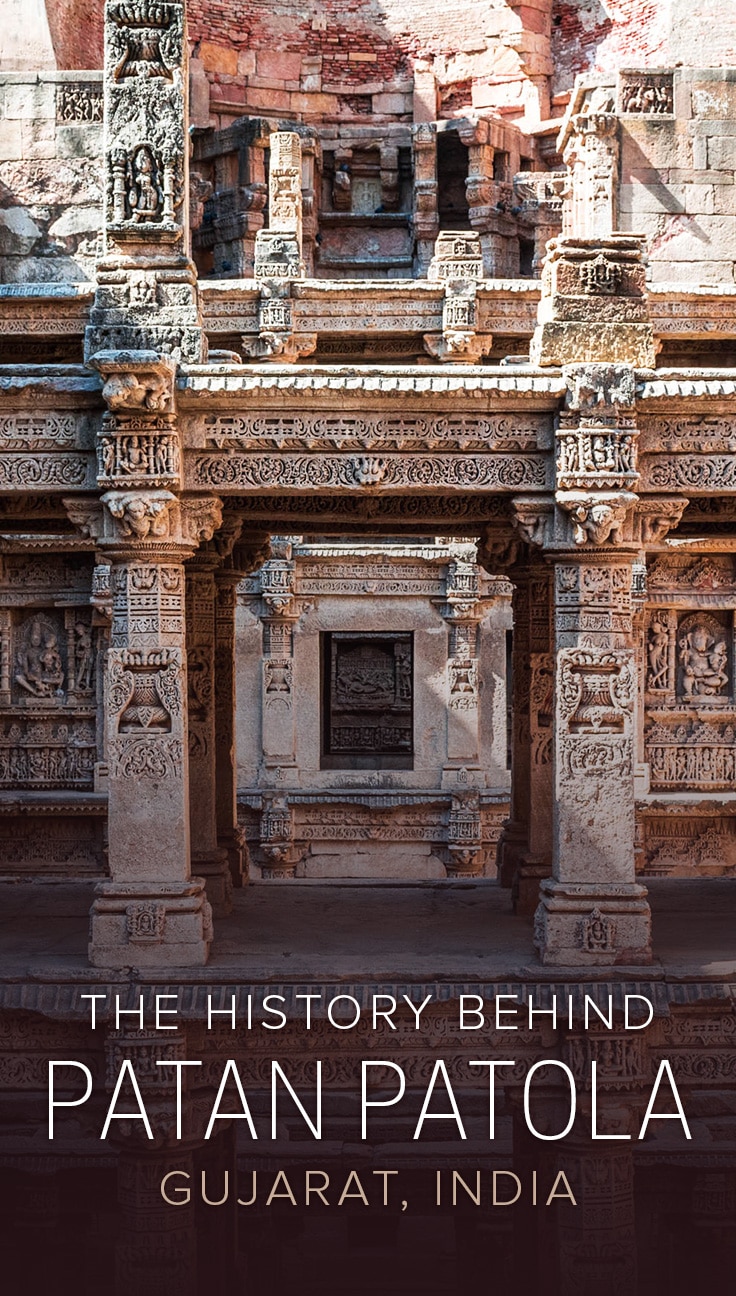

In the 900 years since Kumarpala’s reign, the traditional patterns and practices of Patola making are still alive in Patan. To help me understand how engrained the traditions truly are, Mr. Soni brings me to Rani Ki Vav, an 11th century step well outside of Patan.

To be honest, Patola is the last thing on my mind upon laying eyes on the step well—it is, to say the least, absolutely insane.

The ancient Rani Ki Vav step well outside of Patan by our friend Devanshi Sheth, who connected me with the Soni family.

Seven flights of stairs lead down into the four galleries of the well, once used for the masses to collect their water. Though time has smoothed some, every surface was once intricately carved with patterns or reliefs. Dozens of statues of voluptuous dancers getting dressed adorn one of the walls, while other walls are more divine in nature, showing the different incarnations of Vishnu.

Mr. Soni is patient. He smiles quietly as we foam over the fantastic surroundings, before guiding our attention back to the actual history at hand.

Mr. Soni telling one of the millions of stories engrained in Rani Ki Vav

Walking along the statues of dancers and royals and gods, he explains the historical significance of each curve and edge, before stopping in front of a series of square patterned plates carved into the walls.

Compared to the rest of the graphic step well adornments, they seem almost painfully dull upon first glance. My eyes begin to wander back to the graceful dancers and parading elephants, when Mr. Soni reaches out and brushes the plates with his hand.

Their symmetrical designs are based on the divine positions of the stars, he explains. Impressive given they’re almost 1,000 years old. More amazingly, these are the patterns of those Patola made 900 years ago… and the patterns that are still used today. These traditional designs are what make Patola, Patola.

Patola in the making

Patola of the future

History lesson complete, we return to the workshop, where we’re treated to the sight of half-completed Patola in the making. Massive wooden looms fill more peeling workshops, vibrant silk threads crisscrossing otherwise threadbare rooms. Mr. Soni flits to and fro between the different looms, stopping to adjust some misaligned threads when he espies them. Whenever he does, the others often stop to watch the master at work.

And Mr. Soni truly is a master: despite the numerous people working in each room, Mr. Soni and his son are the only two people in the company that know the entire Patola process.

In all of Patan, only two families of the original 700 still make Patola: the Sonis and the Salvis. The Sonis are open about what they do, but the Salvis are tight-lipped about what goes on within their workshops. They also refuse to pass down the knowledge to anyone but their sons.

Only a million more hours to go!

So does this mean the art of Patola will eventually die? Mr. Soni hopes not. Realizing the importance of tradition, he works together with his son to both bring in fresh blood to the business, and increase Patola’s reach in the world. Some of their Patola have been given to museums, while his son, Shyam, incorporates Patola fabric into more modern clothes and accessories.

Unlike the Salvis, the Sonis open to teaching parts of the Patola-making process to those not native to Patan, so long as they are hard-working and willing. But potential masters are in much shorter supply. Finding someone competent enough to wrap their minds around the highly mathematical designing and dyeing process is no easy task, and so the father and son remain the gatekeepers of the knowledge. For now.

There’s a Gujarati saying, “Though it may suffer wear and tear, a Patola’s design will never perish.”

Hopefully the same can be said about the art.

The Soni family runs Madhvi Handicrafts, one of the few places to purchase authentic Patola in India. You can learn more about their story on their website.

This article was made possible with the help of Devanshi Sheth, who introduced me to the art and the Soni family. Thanks for being awesome!

Magnificent experience. Love your photos and the content. I am surprised that only two people know the entire process. Then again, many companies are probably run that way.

Great to hear from you. Glad you like the article. We were also surprised, but like you said, it’s not as uncommon as it might seem. Cheers.

It is very good sarees. We are proud of you maintain the Indian tradition with so many difficulties in your manufacturing sarees. I thankful to all. Ashok Mehta. B.H.Road. BIRUR-577116, Karnatka.

Great article and insight Alex. I was happy to stumble upon your piece and find out that the Soni family is a lot more open about this painstaking and sacrosanct process.

Thank you, and happy to share! I agree that it’s good they’re so open—it keeps interest in their art alive, and ensures patola will not be lost to the ages 🙂

Very nice information.I liked reading it.Designs are excellent.

Nice designs .want to have one

Just to clarify, only 2 Salvi families are authorized genuine patan patola weavers. which is GI tagged. And don’t know why you have mentioned Salvis are not open, Mr. Rahul Salvi has made PATOLA MUSEUM in Patan where they have showcased entire process of Patola art & son of other family Mr. Nirmal Salvi has poured his blood to make PATOLA art famous all over India. You can read about Nirmal Salvi, all visitors are allowed to visit their production units.

Any contact number

Alex that’s a very insightful article on patola , I am so happy to read about this , , again , I too have heard that the salvia do not impart the knowledge and art of patola making to anyone outside the family ,in this regard , I applaud the Soni family , who are keeping the art alive ,by sharing it with deligent workers

Davansi sheth 8march 2020 wrote article patan patola says that one family makes patola is true in patan four families makes patan patol today one of the famielies satish kantilal salvi patolawala presh k savi patolawala heritage artiest in patola today i received saintkabir award 2009 by dc handloom ministry of textile new delhi

your article just gave me goosebumps and it turns me to go deep into traditional art rather than modern art.. the way patola being vanishing.. youth should know about it and think about preserve it